Are you ready for the wireless web?

Making sense of commercialising new technology and the emergence of early platform models

Software development companies often focused more on the technology and less on how to take their innovations to market. How new software solutions should be packaged and sold, and to whom, in what format, ultimately raises questions of which business model a company should adopt. For the pioneers of the dot-com era, this was a “Blue Ocean”, an opportunity so new that no one quite knew how to best monetize it. Two-sided platform models and advertising as a revenue stream are now key elements of online businesses, but at the start of the millennium, these solutions had not been invented yet. When we talk about the dot-com era nowadays, we tend to focus on the successful big tech companies that were launched at the time, such as Amazon.com or Google. However, most companies from this era either failed or continued to operate at a much smaller scale. For these tech-focused start-ups, developing the commercial side of the company between the stock market boom of 1999 and the subsequent crash of the stock market in 2000 was challenging. These entrepreneurial ventures had to find ways to bring new software to the market in the absence of accepted solutions of how to sell these new tools.

The "post-PC era" referred to the decline in the sale of personal computers in favour of cell phones / mobile phones, tablets, and other handheld devices. Steve Jobs is widely considered to have popularized the term in 2007 with the launch of the first iPhone, but it was coined by MIT scientist David D Clark in 1999 and adopted early on by AuroraTec.

“Content enabler for the post-PC era”

In early March 2000, the CEO of AuroraTec (a pseudonym), Ravi Chowdury was ready to introduce to the press the company's vision for the wireless web, and what they call the "post-PC era". This went beyond launching a new suite of products and AuroraTec’s Chief Marketing Officer, Jennifer Corby, discusses how the company is positioning itself and flags her suggestions in an email to Ravi and the senior team.

From: Jennifer Corby

Sent: Wednesday, March 01, 2000 1:03 PM

To: Lorraine Saunders

Cc: Ravi Chowdury; Sonia Coppola; Sebastian Dobson;

Luke Golden

Subject: Press presentation take 2

Ryan handed me a presentation and told me that this was the one Ravi is using this week. This was new news to me, especially as both myself and our agency advised against using the technology outlook presentation with the press and analysts.

Moreover, the feedback I would have given - had I had a chance to do so - based on the initial meetings we had was that the presentation was still too long and that many of the people we spoke with were likely to be "up" on the wireless web and would want us to be more insightful about the device landscape etc.

Missing are five messages of importance:

*Any definition of the infrastructure required for the wireless web. We do not want to be in a category creation mode. Content enabler is a new category. See discussion below. * Any positioning of us as the company that focuses on active content. Nowhere do we position ourselves as the leader in transactional content.

*Any definition of intelligent rendering - which is our technology advantage *An org chart for the exec team - which would position me to follow up on the initial conversations Ravi has with the press and analysts. Talking about our angels and not talking about our executives signals to all that that we do not have a full executive team and that therefore we are very early stage.

*The fact that we leverage web standards - especially XML.

In addition to these 5 omissions - which I'm sure are oversights - there are 3 messages that I believe to be misguided.

1. Content enabler for the Post-PC era describes what we do but

does not position us in a pre-existing category. It would be

better to entitle the talk - Are you ready for the wireless web? -

as the single biggest point to be made is that it takes content to

make the wireless web a reality, not just a network, devices, and

a browser.

2. "Which device will win? message" is not in our best interest.

Our point of view is that multiple devices will proliferate and

that there will be no single standard. Some analysts think that

the smart phone will win, others that Handle has already won the

battle. Suggesting a single winner is not in our best interest.

3. The architectural diagrams do not make it clear that we pull

content dyanmically from the world wide web. Every single person

we have presented to lately is confused on this point. It is the

reason we switched to the analogy of a man on a treadmill coupled

with a close up of the travelbreak site at the center of the wheel

with devices "hanging off" this central place is to make this

point crystal clear. The diagrams we have are neither really

specific as to our architecture nor are they visual enough to make

the points with a non-technical audience. This is also the place

where we should make the point that HTML can be at the center

(i.e. travelbreak) or XML -to reinforce that we work within

existings standards.

Jennifer Corby

Chief Marketing Officer

AuroraTec

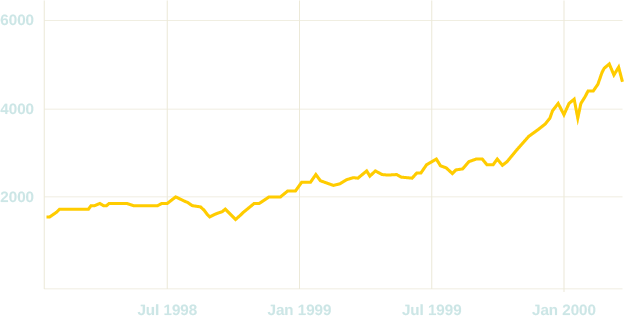

This debate took place when the dot-com boom first began to show signs of being a bubble. Read “It’s all about the Burn Rate” to understand the context and compare this to the NASDAQ performance at the time.

Ravi responded by highlighting that he viewed their PR efforts as successful “based on how widely the market embraces our vision and not based on [the] number of times we get a mention in the press.” He made it clear that he considered Jennifer’s points as details when the future of AuroraTec would likely depend on being successful in the “post-PC era”:

“1. The best way to deliver content in the post-pc era is to use existing HTML content without modifications. Any other approach is […] wasteful.

2. Building device-specific infrastructure is stupid and wasteful. Anyone who recommends this approach is self-serving! There will be a plenty of devices that will be used for access including voice phones.

3. Providing mobile commerce (transaction-oriented stuff) is the key to [the] success of wireless internet. Not sports, news and weather. You can always buy a $0.25 newspaper for that.

4. A successful wireless portal is not the one that provides access to 20-30 brand name websites. It is the one that allows every individual to choose any website that he/she wants to go to.

5. Finally speed and costs matter. If you are going to take 3 months to enable a site and have to maintain it everytime [sic] the website changes, you may as well forget about [the] wireless web.”

NASDAQ daily closing value

(January 1998 - March 2000)

Monetizing software

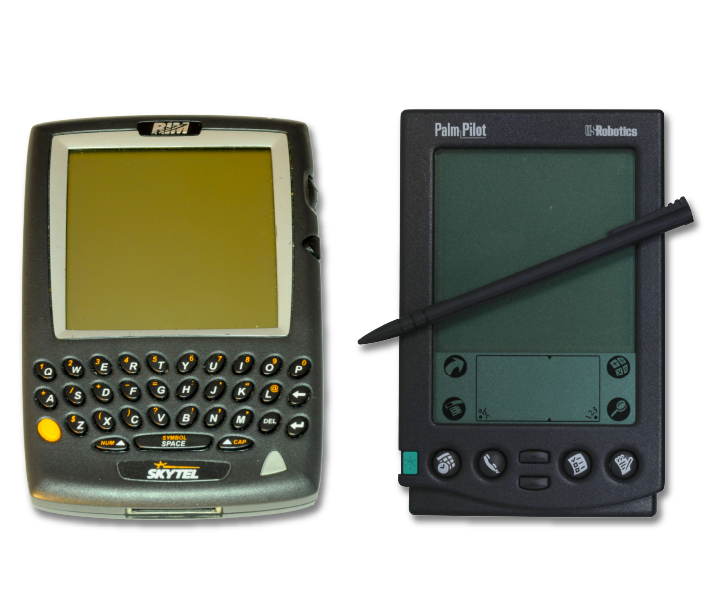

In March 2000 AuroraTec was getting ready to launch new wireless software solutions that bring the internet from the PC to handheld wireless devices such as Palm Pilots, Blackberries, and mobile / cell phones, known as the AuroraTec Rendering Tool, or ART. But selling this type of software was different from selling something from a software tool that did specific things for consumers, say a word processing programme. Key people at AuroraTec were discussing how to monetize the ART, which was a software solution that helped to create a digital infrastructure accessible to a range of different devices. Some at AuroraTec were concerned that selling a core software outright carried the risk of selling the company and its intellectual property (IP) with it. How should they price a software solution, considering those risks?

If you want to know more about IP and how AuroraTec debated how to use and protect its intangible resources, see Did the Internet kill strategy?

Left: Jarek Tuszyński, CC BY 4.0. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Right: Rama & Musée Bolo - Own work, CC BY-SA 2.0 fr. Credit:

Wikimedia Commons

From: Jennifer Corby

Sent: Tue, 21 Mar 2000 16:50:35 -0800

To: Ira Lo, Cathy Craven, Rick O’Connor, Lorraine Saunders,

Sebastian Dobson, Hesther Club, Jacob Wong, Lori Hume, Ravi

Chowdury, Doug Roberts

Subject: Suitcase plan to license software

We have prepared preliminary pricing to license the AuroraTec Content Server (ECS) and AuroraTec Rendering Tool (ART) for resale purposes. This price list starts at $1 M and tops out at $6 M before the cost of hardware. Which means that clearly this pricing is not for everyone. Even so, it is a great start and we will have an opportunity to get some quick, real world feedback on this from Ira when she presents it to Buy.Soon. Background

ShopNow has 5000 sites on their network, 1000 sites that they developed on a custom basis and 4000 that use a template driven engine.

They believe that their top 1000 sites would be most interested in going wireless and want to offer this capability in conjunction with AuroraTec. We'd provide them with the ECS preconfigured and pre-installed on an appropriate hardware platform. (Today this means NT but we will be moving to Sun Solaris very very quickly.) We will also support them with 2 people to be located on site for service and support purposes - for the first 6 weeks. ShopNow will provide all hosting services to their customers; we will provide all rendering.

Next Steps:

Ira to formalize in a proposal. You may wish to get with

Jacob/Hesther to review some of the QR contract terms which would

apply to your situation as well. For example - regarding a

referral of acustomer by us to ShopNow for hosting purposes.

Ira - feel free to call me tomorrow (I'll be working from home in the p.m.) if you have any questions. Use my cell phone number.

Luke to get with Doug and pick up/adapt software license Julie Shevlin started. Luke to put formal signature matrix on this pricing and get approval through Sales, Marketing, Finance, and Ravi.

Jennifer Corby

Chief Marketing Officer

AuroraTec

From: Doug Roberts

Sent: Tuesday, March 21, 2000 6:52 PM

To: Ira Lo; Rob Silverton; Jennifer Corby; Cathy Craven; Lorraine

Saunders; Rick O’Connor; Jacob Wong; Ravi Chowdury; Lori Hume;

Sebastian Dobson; Hesther Club; Doug R¬oberts

Subject: Re: Suitcase plan to license software

Jennifer -

2 issues to consider:

1) we should also get a % of transaction revenue for our long term

valuation(small is ok, but something needs to be retained)

2)we should also get some % (50%)of revenues if they opt to become

an ASP (or we get the content they mobilize in the process of

becommeing an ASP)...else we are selling the company for a few

million bucks

Doug Roberts

VP - Global Telecom Business Unit

AuroraTec